At this point in my book analysis of Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, in this post, I’m going to provide brief overviews of both Chapter 3 (“Human Equality, Cultural Superiority, and Racism”) and Chapter 4 (“Land, Settlers, and Conquest”). I want to write no more than two posts after this one.

Chapter 3: Human Equality, Cultural Superiority, and “Racism”

The fundamental question Biggar addresses in Chapter 3 is: “Was the British Empire centrally, essentially racist?” Before he gets into any specifics regarding the British Empire, though, he briefly discusses the definition of “racism.” Essentially, he defines racism as something that “pre-judges the individual by regarding him or her simply as a member of a group, automatically attributing to the individual that group’s supposed characteristics, which are stereotyped in unflattering terms” (68).

What often happens Biggar argues, though, is that “racism” is broadened to criticizing any other culture or morals, specifically, if a “white person”—European or American—criticizes some cultural practice in some region of Africa, or India, or Asia, or South America. That, some people claim is to be racist. Biggar disagrees because some cultures are, in fact, more advanced than others, be it technologically, morally, whatever. To acknowledge those points of cultural inferiority of some cultures—as long as one “attributes cultural inferiority to lack of development, rather than biological nature” (70)—is not racist.

Therefore, Biggar argues that the British Empire was not, at its core, racist—it did not believe that the people of India or Africa were racially inferior. That being said, the British Empire did view its own culture as more advanced and civilized. In addition, the same Christian conviction that God created all human beings equal that led to the abolition of slavery throughout the Empire in the early 1800s also, then turned its sights to the places throughout the world where Britain had established trade and sought “to Christianize, civilize, and modernize indigenous peoples in the first half of the nineteenth century” (71).

Throughout the rest of Chapter 3, Biggar highlights the cultural differences and challenges that accompanied all this. For brevity’s sake, I will simply bullet-point what I feel are his most significant points:

- The cultural differences between the British in India and the people of India were significant to the point where neither group ended up interacting that much with each other socially. Conservative Hindus, for example, resented the British attempt to abolish customs like child marriage and female infanticide. The British came across as high-handed and the Hindus came to view the British like Untouchables.

- The British who came to India after around 1860 did, in fact, hold to more clearly racial attitudes toward the Indians. Indians like even Gandhi noticed a radical difference between racial attitudes among the British back in London, where Indians were respected and treated kindly, and the those living in India, who saw Indians as “black bastards.”

- The Egyptian culture was very different than the culture of the British. Biggar points out how Egyptians were astounded to find that British aristocrats felt it was their duty to go into the army, because rich Egyptian families were always able to keep their children out of military duty.

- Some of the cultural practices the British saw as more barbaric and un-Christian were female infanticide, child sacrifice, sati (the practice of widows immolating themselves on the funeral pyres of their deceased husbands, so that relatives wouldn’t have to bear the burden of taking care of them), female genital mutilation, and not to mention slavery.

- Many in India and Africa converted to Christianity, not because of forced coercion, but because they were attracted to Christianity and the more civilized culture of the British.

- Cultures are never static—there are always cultures that rub up against each other and influence one another. And while we can agree that individuals should not be forced to adopt foreign beliefs and practices, we should also agree that communities should not prevent individuals from doing so.

- Even those who have criticized British colonialism on a number of issues, they also recognized that its legacy is complicated, with both things that are good as well as bad.

- Biggar ends the main part of Chapter 3 this way: “…the British Empire did contain some appalling racial prejudice, but not only that. It also contained respect, admiration and genuine, well-informed, costly benevolence. Indeed, from the opening of the 1800s until its end, the empire’s policies towards slaves and native peoples were driven by the conviction of the basic human equality of the members of all races. It cannot be fairly said, therefore, that the empire was centrally, essentially racist” (91).

- He ends the chapter by commenting on the conclusion of the Imperial War Graves Commission of 2021. It claimed that thousands of Indians and Africans who had died during WWI fighting for Britain were not properly commemorated with gravestones. This was decried widely, with some calling it “apartheid in death” and a clear example of British racist imperialism. Biggar points out, though that in Europe, fallen soldiers, regardless of their race, were commemorated with both marked individual graves and collective memorials. Outside of Europe, though, in places in Africa, where there were cultures did not practice the formal burial of the dead as in Europe, Britain respected those customs and did not, therefore, commemorate the fallen dead soldiers with individual graves. Simply put, in those cases, the lack of gravestones was a result of respecting the practices of those foreign cultures.

Chapter 4: Land, Settlers, and Conquest

The accusation Biggar addresses in Chapter 4 is the charge that Britain forcibly took the land from native peoples through naked conquest and thereby ignored the natives’ right to the land. The claim is that before the colonists came to the Americas, the indigenous people generally lived in harmony and shared the land from time immemorial. The brutal conquest and displacement of people only came when the Europeans came and took over.

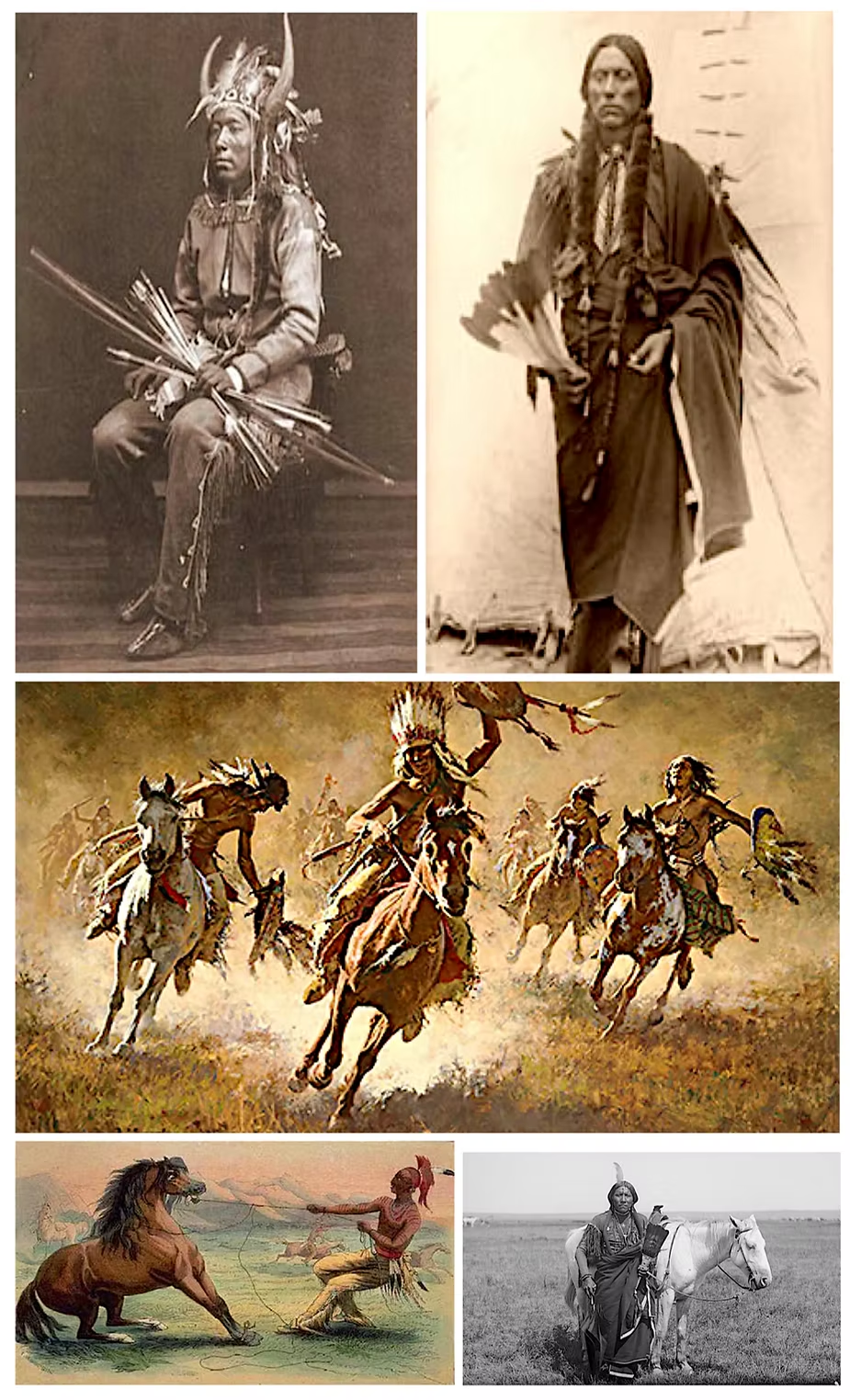

Biggar argues that such a depiction of the native peoples of the Americas is simply not true. The Comanche “obliterated the Apache civilization from the Great Plains and carved out a vast territory that was larger that the entire European-controlled area north of the Rio Grande at the time” (101). The Montagnais displaced the Iroquois in the late 1500s, but then later on the Iroquois came back to reconquer the St. Lawrence Valley and spread all the way to present-day Illinois in the 1600s. Biggar notes other examples as well, but the point is clear: the native Indian peoples often went to war with each other, displaced each other, and took over their land.

The second point Biggar makes in this chapter is that the British primarily acquired land through treaties, not conquest. As I did with Chapter 3, I will now bullet-point the major points Biggar makes in Chapter 4:

- Biggar first responds to the charge by Adeyke Adebajo that Cecil Rhodes forcibly displaced black people from their ancestral lands in South Africa. Biggar argues that the Ndebele King, Lobengula, signed a concession for Rhodes’ South African company to mine for minerals in Mashonaland. Yet when Ndebele raiding parties ignored their chief’s orders to avoid the white settlers and attacked, Rhodes’ company retaliated and came to take over the land that came to be known as Rhodesia (modern day Zimbabwe). Besides, the land hadn’t belonged to the Ndebele long before—they had seized it from the Shona fifty years earlier, and had systematically tortured and slaughtered the Shona.

- In North America, the British bound themselves to treaties with the native population. In 1763, King George issued a Royal Proclamation that the land west of the Appalachian and Allegheny Mountains up to the Mississippi River was reserved for the native tribes and that the colonists were not to settle there. That proclamation, actually, was one of the things that incited the colonists to revolt against Britain and led to the American Revolution.

- In 1787, the newly formed United States issued the Northwest Ordinance looked to open up the western lands for settlement but pledged not to take any of the land without the consent of the Indians. Biggar notes that the intent and principle was to only take lands through treaties and native consent, but in the actual implementation there ended up being many violations and cruelty.

- That being said, Biggar notes that the major reason for the decimation of the native populations in North America was not European, British, or American conquest, but rather European diseases that were a result of coming in contact with the Europeans. While this was tragic, Biggar argues, we cannot count that as some sort of genocide that the Europeans purposely inflicted on them.

- Biggar talks about the British treaties that led to their colonization of New Zealand, particularly among the Maori. Long story short, the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi involved 540 Maori chiefs agreeing to British sovereignty of the land while them being able to retain autonomy. When, over time, the British violated the treaty, the Maori were able to appeal, and the British had to pay compensation.

- When the British landed in Australia, they thought it was uninhabited. Eventually, when it was discovered the Aboriginal tribes did live there, Parliament set up a committee to make sure they were protected and had access to education.

- In 1790, the United States government enacted the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act, that prohibited the sale of tribal lands without the consent of the federal government—but the 13 states proceeded to ignore it and basically did what they wanted anyway.

- In summary, Biggar emphasizes (A) the impact European diseases had on the native populations, (B) the fact that sometimes colonists honestly thought the land was unoccupied, and (C) that “the normal imperial means of land transfer…was not by conquest, but by treaty” (123). Still, it is true that sometimes treaties were broken and sometimes settlers on the frontier, away from any real government control, did in fact forcibly take land from the natives.

Concluding Thoughts on Chapters 3-4

One can easily take issue with a number of Biggar’s arguments and say that he is giving a skewed version of the historical examples he gives in these chapters. Still, we must remember that the purpose of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning is not to provide a complete historical account of the history of the British Empire. As Biggar stated at the beginning of his book, and as he will re-emphasize at the end, the book is specifically answering the charges that current “anti-colonialist” groups have leveled against the British Empire and its colonialism.

Therefore, with Chapter 3, the charge was that the British Empire was essentially racist—that it was the driving motivator in his colonial expansion. Biggar argues that it wasn’t and, I believe, makes a convincing case. Again, he does not deny that racism existed—he is simply saying that the British colonial enterprise was not driven by racism, as is often charged. Secondly, he acknowledges that the British felt their culture that was deeply influenced by Christianity was superior to other cultures in a variety of ways—but that is not the same thing as racism. On top of that, in many ways it was true. After all, the British Empire abolished slavery, therefore, if one think slavery is immoral, then one has to conclude that the British culture that abolished slavery was morally superior to other cultures that still practiced slavery.

In Chapter 4, the main charge Biggar addressed was that the British Empire used naked force and conquest to essentially steal land from native populations. Again, Biggar shows that was not true—the main way it acquired land was through treaties. Again, he does not deny that sometimes colonists and settlers did, in fact, use naked force and conquest; and he does not deny that sometimes the British were guilty of breaking treaties. But he does show that the primary and preferred way the British acquired land was through negotiations and treaties. Again, the specific charge was in relation to how the British went about acquiring land, not whether or not it ever used unjustifiable force and conquest.

And so, there is no question that there are many points of legitimate debate regarding what Biggar presents in these two chapters. Still, there are two things to remember: (1) that Biggar is answering two specific charges, and (2) Biggar readily acknowledges that there was racism involved in Britain’s colonial project and that there were many instances of unjustifiable force. The reason this is important to emphasize will become more apparent by the end of this book analysis series.